Cooper Campbell

Instruments

September 19 – October 30, 2021

Opens Sunday, September 19th: 4-8PM

hosted by

eyes never sleep

by appointment only

to make an appointment, please schedule through this: link.

![]()

Instruments

September 19 – October 30, 2021

Opens Sunday, September 19th: 4-8PM

hosted by

eyes never sleep

by appointment only

to make an appointment, please schedule through this: link.

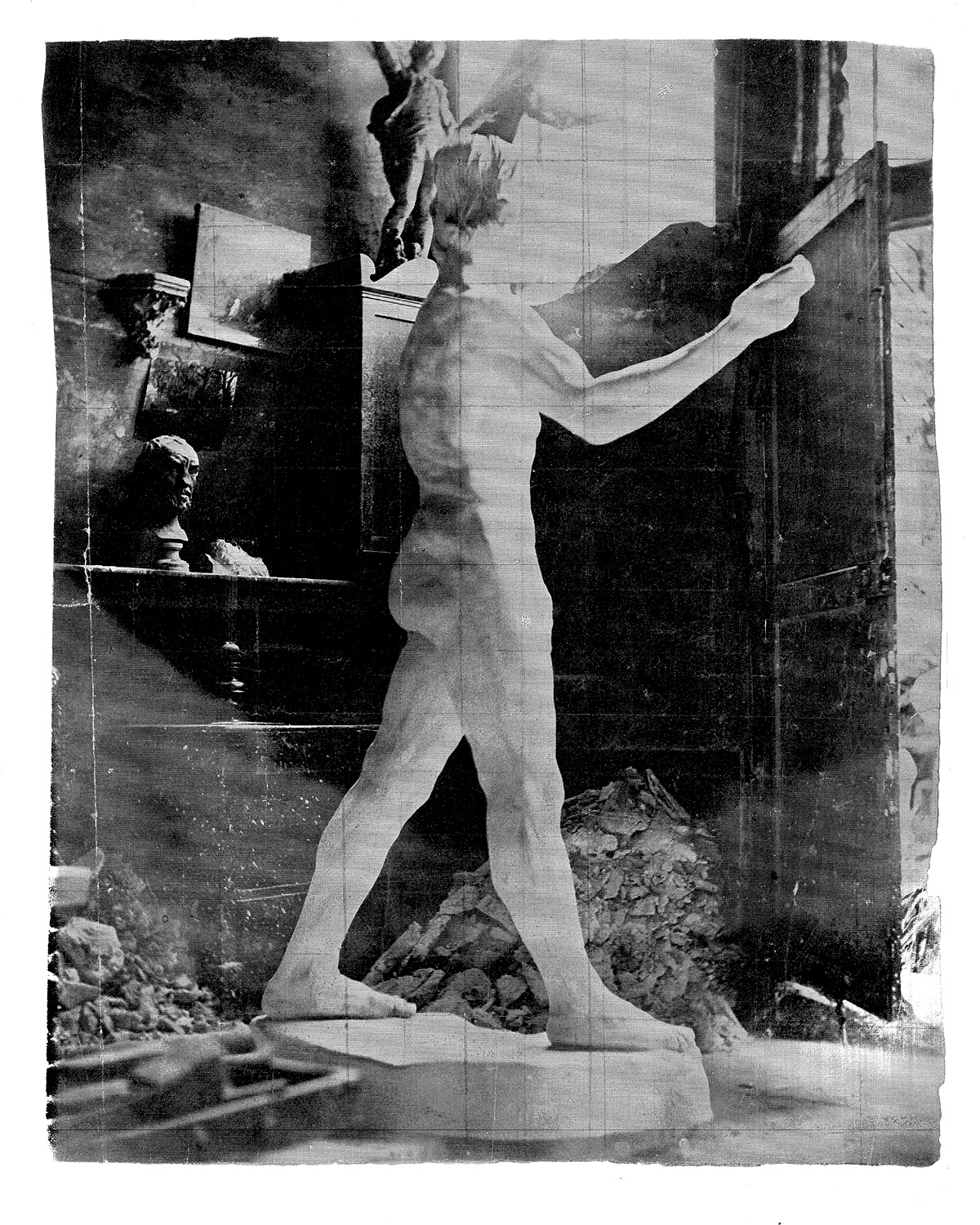

Image: Freuler, D. View of the penultimate plaster of St. John the Baptist Preaching (1878-1880) by Auguste Rodin. 1878. Albumen print with graphite. Musée Rodin, Paris/Meudon. In Rodin’s Studio: A Photographic Record of Sculpture in the Making. Elsen, Albert Edward. Oxford: Phaidon Press; Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; in association with Musée Rodin, 1980. 41, Print.

Presented as both an exhibition of artworks and as a book that compiles original writing and archival images, Instruments represents Cooper Campbell’s research into the practice of valuation. In tandem with the release of the book, the exhibition takes place at eyes never sleep, an apartment exhibition space on the Upper East Side of Manhattan founded by Colin Ross, a director at a prominent gallery on Madison Avenue. The decision to situate Instruments in an art dealer’s home was an intentional one; Campbell has embedded these works within Ross’s domestic space to invoke an appraisal of the art industry’s participants themselves.

The title Instruments is derived from the term’s financial definition: monetary contracts between parties that can be created, traded, modified, and settled. Campbell’s interests in the monetization of art have urged him to examine the art market’s role in the accumulation of wealth. An analogy to alchemy is present in Campbell’s research—what is the definition of value, and how does one issue, institutionalize, or otherwise invent value from raw material alone?

Within the contemporary art world, creating a limited edition of a replicable art object is a widely accepted practice. The sales structure of nineteenth-century French Modernist Auguste Rodin’s artworks set a legal, financial, and cultural model for dispersing the concept of an original work of art, a precedent that remains a fundamental component to today’s art industry. After Rodin’s death in 1917, the French government inherited his intellectual property rights, formed Musée Rodin as a governing body of his estate, and began to posthumously produce Rodin’s sculptures in editions of twelve. By implementing traditional casting and scaling methods to replicate the same object in multiples, it became possible to profit numerous times from the sale of what was, in essence, the same artwork. Mid-century financiers were particularly passionate about collecting Rodin’s works, and Campbell’s essay illuminates unmistakable parallels between Rodin’s market structure and the world of securities trading. In tracing this contour, Campbell finds both markets to be realms impacted, commingled, and determined behind the scenes by the influence of singular individuals and private third parties.

To illustrate the phenomenon of valuation, Campbell has rendered disparate financial devices as his own artworks. Collectively these instruments question the systems of value creation, and the blurriness surrounding originality. Multiple systems are considered: spot prices (the constantly shifting values of copper, nickel, and tin on the commodities market); numismatic value (a coin collector’s valuations based on a coin’s rarity and historical importance); contractual value (a consignment, an IOU, a promise); novel value (an original versus an edition versus a copy); and retail value (the number on a price tag), amongst others. His interrogations of these orders of value take the form of material interventions, such as a nineteenth-century ormolu vase displaying a bouquet with gentian (a French flower used as a barometer for bitterness); and a surmoulage (an unauthorized cast of an original authorized casting) of Rodin’s Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, 1897 with the casting sprues still attached to the work. Both in concert and in conflict, the objects within Instruments gesture to cracks and circularities within the logic of value.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Pointing Machine (Macchinetta di Punta)

Cooper Campbell

With assistance from Richard Zeemer

After John Bacon the Elder RA, Antonio Canova, Nicholas-Marie Gatteaux

Late 18th Century / 2018-2020

Brass, steel

Dimensions variable, approx. 24 x18 x 12 inches

By the late eighteenth century the classic sculptor of high fame, whose mind must necessarily be engaged upon his designs in clay or wax, employed assistants to give permanence to his oeuvre. Sculptors of this type were so persuaded of their genius that they expressed some condescension towards those craftsmen upon whom they were now dependent. [1]

A Pointing Machine is a device used to fabricate one-to-one copies of existent sculptures in subtractive materials (stone, wood, plaster, etc). The device describes the three-dimensional form of a work by measuring points along its surface in relation to each other. The ability to precisely measure and transfer three-dimensional forms allowed the sculptor to contract the labor of production to unskilled or less skilled craftsmen.

Three primary needles allow a carver to establish a fixed position on the work they wish to copy and the material they wish to copy the work onto. From this fixed position the carver may create exact measurements of the form using a fourth needle seated in a spring loaded saddle at the end of an articulated arm. The sculptor thereby transfers the spatial data of a pre-existing form onto a new block of material to a high degree of precision.

Evidence of the employment of primitive versions of the pointing machine have been observed in Greek and Roman sculptural practice. However, the earliest known example of a modern Pointing Machine was produced by the French Medalist Nicholas-Marie Gatteaux (1751-1832) sometime in the late 1700’s though the English Sculpture and Porcelain manufacturer John Bacon (1740-1799) produced a similar device in the same era that he later gifted to the Italian artist Antonio Canova (1757-1822) who perfected the device and popularized its usage.

[1] Ayres, James. “The Pointing Machine.” Art, Artisans and Apprentices: Apprentice Painters & Sculptors in the Early Modern British Tradition, Illustrated, Oxbow Books, 2014, p. 335.

![]()

![]()

American Coinage

Cooper Campbell with Thomas Lunt

1860-1978/2020

Cardboard, copper, gold, silver, steel

Dimensions variable

Long before the advent of coinage, ancient civilizations utilized gold and silver in the form of jewelry, art, and ingots. These metals were measured and valued by weight. Sumerian clay tablets reveal that as far back as 2400 B.C.E., official standards existed for the weighing of silver for use as money. The same was true throughout the ancient world. One of the earliest passages in the Old Testament reports that Abraham “weighed to Ephron... four hundred shekels of silver, current money” to buy a burial plot for his wife, Sarah. [1]

Money in the form of coins first made its appearance in Lydia [2] around 640 B.C.E. The first coins were made of a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver called electrum. A government symbol on each coin attested that it weighed the proper amount. Merchants found these ingot coins more convenient than bringing out the scales to weigh silver in every transaction. About a century later, King Croesus, the most famous Lydian king, decreed that all official coins had to be minted in either refined gold or silver. This manner of coinage persisted for over 2,500 years because of the durability, scarcity, uniformity, and divisibility of these metals. They were a measure of value, an easy way to transfer and preserve wealth, and readily accepted for services and commodities worldwide. [3]

There are three primary forms of money. Commodity money has inherent value such as salt, cocoa beans, and tobacco or the exchange of precious metals like gold, silver, and copper. Representative currency functions as a certificate, its value being generated by its function as a guarantee of a predetermined amount of a select commodity. The third form is called fiat currency, money whose value is expressed through social agreement.

The coins in American Coinage are all examples of partially representative money, these coins (save for a limited pressing of steel pennies issued during a copper scarcity caused by WWII) are all partial commodity tokens. The face value or intended value of the coins is divorced from their material commodity value via the decoupling of US’s dollar from the gold standard. Additionally the influence of perceived scarcity has distorted the value of these coins, creating a third form of numismatic value or collectability.

There is no static value for these coins due to the fluctuations of the value of the dollar, the precious metals markets, and the numismatic markets. All continually reappraise the value of these coins.

[1] Genesis 23:16. The shekel was a hebrew unit of weight.

[2] An ancient Kingdom Located in what is now Turkey.

[3] Foster, Ralph. Fiat Paper Money: The History and Evolution of our Currency . Foster Publishing. Kindle Edition.

![]()

![]()

Surmoulage

Cooper Campbell, with assistance from Firebird Bronze Foundry, Portland OR. After Auguste Rodin with Rudier Foundry, Sculptures LTD.

1897, 1965-1975 (approx), 2020

Bronze

12 x 6 x 8 inches

Editon of 12 + 1 AP

This work is a surmoulage [1] of Rodin’s Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, (1897). Surmoulage is reproduced from a resin edition produced by Sculptures LTD a company that specialized in low cost resin editions of minor works by canonical Western artists.

This casting is not a true edition. Despite the casting having Rodin’s signature as well as the foundry mark from the artist’s lifetime foundry [2], leaving the sprue system attached and the bronze un-patinated disallows the intended authorship of Rodin while still retaining the form of the intended work. [3]

The original work Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, (1897) by Auguste Rodin is a study for the Monument to Balzac (1891–1897), a public commission from Société des Gens de Lettres de France. Following the initial display in 1898 at the Salon at Champ de Mars, the work was rejected by the Société and the plaster was moved to Rodin’s studio at Meudon where it was displayed for the next forty years before being editioned in bronze in 1939, twenty- two years after the artist’s death.

Often referred to as the first modern sculpture, monumental bronze castings can be found in the collections of The Norton Simon Museum of Art (Pasadena, California, U.S.), the Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden (Washington D.C, U.S.), the Museum of Modern Art in (New York City, New York, U.S.), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, (Los Angeles, California, U.S.), the Middelheim Open Air Sculpture Museum (Antwerp, Belgium), the Musée Rodin (Meudon, France), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands), Hakone Open-Air Museum (Ashigarashimo District, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan), the National Gallery of Victoria in (Melbourne, Australia), and in public installation at the intersection between Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard du Montparnasse, (Paris, France) as well as in the open spaces around the former Ateneo de Caracas (Caracas, Venezuela). Evidence suggests two additional castings; one somewhere in the U.S. and another in Europe.

Bronze editions of Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac (1897) were initially cast by Georges Rudier nearly fifty years after Rodin’s death, from the plaster studies made in preparation for the monument and left behind in the artist’s studio. The study can be found at the Musée Rodin (Meudon, France) with editions found in the collections of Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.), Baltimore Museum of Art (Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.), Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, Virgina, U.S.), Legion of Honor (San Francisco, California, U.S.), Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, (South Hadley, Massachusetts, U.S.), The Hirschorn, (Washington, D.C., U.S.), The Kreeger Museum (Washington, D.C., U.S., two copies in the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., U.S.), Maryhill Museum of Art (Goldendale, Oregon, U.S.), the Brooklyn Museum (New York City, New York, U.S.), McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College (Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.), The Museum of Modern Art, (New York City, New York, U.S.) as well as a plaster at the Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas, Texas, U.S.).

[1] An unauthorized cast of an original authorized casting.

[2] Alexis Rudier.

[3] This is to protect Campbell from encroachments of Rodin’s authorship.

![]()

Dross

Cooper Campbell

2020

Bronze, unknown heavy metals

9 x 9 x 6 inches

Dross is the term for material impurities of a given alloy or metal that has formed on the surface of liquid metal during the casting process. They are primarily oxides that are produced by the extreme heat necessary for the casting process—as well as tertiary contaminants that may exist in the casting stock.

Dross is absolute waste. Due to its unreliable and unknown make up it is unusable in any continued casting process and unrecyclable as a byproduct.

Dross is a concretion of this cast off and waste materials bound into a consolidated mass by a matrix of bronze.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

---

Presented as both an exhibition of artworks and as a book that compiles original writing and archival images, Instruments represents Cooper Campbell’s research into the practice of valuation. In tandem with the release of the book, the exhibition takes place at eyes never sleep, an apartment exhibition space on the Upper East Side of Manhattan founded by Colin Ross, a director at a prominent gallery on Madison Avenue. The decision to situate Instruments in an art dealer’s home was an intentional one; Campbell has embedded these works within Ross’s domestic space to invoke an appraisal of the art industry’s participants themselves.

The title Instruments is derived from the term’s financial definition: monetary contracts between parties that can be created, traded, modified, and settled. Campbell’s interests in the monetization of art have urged him to examine the art market’s role in the accumulation of wealth. An analogy to alchemy is present in Campbell’s research—what is the definition of value, and how does one issue, institutionalize, or otherwise invent value from raw material alone?

Within the contemporary art world, creating a limited edition of a replicable art object is a widely accepted practice. The sales structure of nineteenth-century French Modernist Auguste Rodin’s artworks set a legal, financial, and cultural model for dispersing the concept of an original work of art, a precedent that remains a fundamental component to today’s art industry. After Rodin’s death in 1917, the French government inherited his intellectual property rights, formed Musée Rodin as a governing body of his estate, and began to posthumously produce Rodin’s sculptures in editions of twelve. By implementing traditional casting and scaling methods to replicate the same object in multiples, it became possible to profit numerous times from the sale of what was, in essence, the same artwork. Mid-century financiers were particularly passionate about collecting Rodin’s works, and Campbell’s essay illuminates unmistakable parallels between Rodin’s market structure and the world of securities trading. In tracing this contour, Campbell finds both markets to be realms impacted, commingled, and determined behind the scenes by the influence of singular individuals and private third parties.

To illustrate the phenomenon of valuation, Campbell has rendered disparate financial devices as his own artworks. Collectively these instruments question the systems of value creation, and the blurriness surrounding originality. Multiple systems are considered: spot prices (the constantly shifting values of copper, nickel, and tin on the commodities market); numismatic value (a coin collector’s valuations based on a coin’s rarity and historical importance); contractual value (a consignment, an IOU, a promise); novel value (an original versus an edition versus a copy); and retail value (the number on a price tag), amongst others. His interrogations of these orders of value take the form of material interventions, such as a nineteenth-century ormolu vase displaying a bouquet with gentian (a French flower used as a barometer for bitterness); and a surmoulage (an unauthorized cast of an original authorized casting) of Rodin’s Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, 1897 with the casting sprues still attached to the work. Both in concert and in conflict, the objects within Instruments gesture to cracks and circularities within the logic of value.

Pointing Machine (Macchinetta di Punta)

Cooper Campbell

With assistance from Richard Zeemer

After John Bacon the Elder RA, Antonio Canova, Nicholas-Marie Gatteaux

Late 18th Century / 2018-2020

Brass, steel

Dimensions variable, approx. 24 x18 x 12 inches

By the late eighteenth century the classic sculptor of high fame, whose mind must necessarily be engaged upon his designs in clay or wax, employed assistants to give permanence to his oeuvre. Sculptors of this type were so persuaded of their genius that they expressed some condescension towards those craftsmen upon whom they were now dependent. [1]

A Pointing Machine is a device used to fabricate one-to-one copies of existent sculptures in subtractive materials (stone, wood, plaster, etc). The device describes the three-dimensional form of a work by measuring points along its surface in relation to each other. The ability to precisely measure and transfer three-dimensional forms allowed the sculptor to contract the labor of production to unskilled or less skilled craftsmen.

Three primary needles allow a carver to establish a fixed position on the work they wish to copy and the material they wish to copy the work onto. From this fixed position the carver may create exact measurements of the form using a fourth needle seated in a spring loaded saddle at the end of an articulated arm. The sculptor thereby transfers the spatial data of a pre-existing form onto a new block of material to a high degree of precision.

Evidence of the employment of primitive versions of the pointing machine have been observed in Greek and Roman sculptural practice. However, the earliest known example of a modern Pointing Machine was produced by the French Medalist Nicholas-Marie Gatteaux (1751-1832) sometime in the late 1700’s though the English Sculpture and Porcelain manufacturer John Bacon (1740-1799) produced a similar device in the same era that he later gifted to the Italian artist Antonio Canova (1757-1822) who perfected the device and popularized its usage.

[1] Ayres, James. “The Pointing Machine.” Art, Artisans and Apprentices: Apprentice Painters & Sculptors in the Early Modern British Tradition, Illustrated, Oxbow Books, 2014, p. 335.

American Coinage

Cooper Campbell with Thomas Lunt

1860-1978/2020

Cardboard, copper, gold, silver, steel

Dimensions variable

Long before the advent of coinage, ancient civilizations utilized gold and silver in the form of jewelry, art, and ingots. These metals were measured and valued by weight. Sumerian clay tablets reveal that as far back as 2400 B.C.E., official standards existed for the weighing of silver for use as money. The same was true throughout the ancient world. One of the earliest passages in the Old Testament reports that Abraham “weighed to Ephron... four hundred shekels of silver, current money” to buy a burial plot for his wife, Sarah. [1]

Money in the form of coins first made its appearance in Lydia [2] around 640 B.C.E. The first coins were made of a naturally occurring alloy of gold and silver called electrum. A government symbol on each coin attested that it weighed the proper amount. Merchants found these ingot coins more convenient than bringing out the scales to weigh silver in every transaction. About a century later, King Croesus, the most famous Lydian king, decreed that all official coins had to be minted in either refined gold or silver. This manner of coinage persisted for over 2,500 years because of the durability, scarcity, uniformity, and divisibility of these metals. They were a measure of value, an easy way to transfer and preserve wealth, and readily accepted for services and commodities worldwide. [3]

There are three primary forms of money. Commodity money has inherent value such as salt, cocoa beans, and tobacco or the exchange of precious metals like gold, silver, and copper. Representative currency functions as a certificate, its value being generated by its function as a guarantee of a predetermined amount of a select commodity. The third form is called fiat currency, money whose value is expressed through social agreement.

The coins in American Coinage are all examples of partially representative money, these coins (save for a limited pressing of steel pennies issued during a copper scarcity caused by WWII) are all partial commodity tokens. The face value or intended value of the coins is divorced from their material commodity value via the decoupling of US’s dollar from the gold standard. Additionally the influence of perceived scarcity has distorted the value of these coins, creating a third form of numismatic value or collectability.

There is no static value for these coins due to the fluctuations of the value of the dollar, the precious metals markets, and the numismatic markets. All continually reappraise the value of these coins.

[1] Genesis 23:16. The shekel was a hebrew unit of weight.

[2] An ancient Kingdom Located in what is now Turkey.

[3] Foster, Ralph. Fiat Paper Money: The History and Evolution of our Currency . Foster Publishing. Kindle Edition.

Surmoulage

Cooper Campbell, with assistance from Firebird Bronze Foundry, Portland OR. After Auguste Rodin with Rudier Foundry, Sculptures LTD.

1897, 1965-1975 (approx), 2020

Bronze

12 x 6 x 8 inches

Editon of 12 + 1 AP

This work is a surmoulage [1] of Rodin’s Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, (1897). Surmoulage is reproduced from a resin edition produced by Sculptures LTD a company that specialized in low cost resin editions of minor works by canonical Western artists.

This casting is not a true edition. Despite the casting having Rodin’s signature as well as the foundry mark from the artist’s lifetime foundry [2], leaving the sprue system attached and the bronze un-patinated disallows the intended authorship of Rodin while still retaining the form of the intended work. [3]

The original work Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac, (1897) by Auguste Rodin is a study for the Monument to Balzac (1891–1897), a public commission from Société des Gens de Lettres de France. Following the initial display in 1898 at the Salon at Champ de Mars, the work was rejected by the Société and the plaster was moved to Rodin’s studio at Meudon where it was displayed for the next forty years before being editioned in bronze in 1939, twenty- two years after the artist’s death.

Often referred to as the first modern sculpture, monumental bronze castings can be found in the collections of The Norton Simon Museum of Art (Pasadena, California, U.S.), the Hirshhorn Museum Sculpture Garden (Washington D.C, U.S.), the Museum of Modern Art in (New York City, New York, U.S.), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, (Los Angeles, California, U.S.), the Middelheim Open Air Sculpture Museum (Antwerp, Belgium), the Musée Rodin (Meudon, France), the Van Abbemuseum (Eindhoven, Netherlands), Hakone Open-Air Museum (Ashigarashimo District, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan), the National Gallery of Victoria in (Melbourne, Australia), and in public installation at the intersection between Boulevard Raspail and Boulevard du Montparnasse, (Paris, France) as well as in the open spaces around the former Ateneo de Caracas (Caracas, Venezuela). Evidence suggests two additional castings; one somewhere in the U.S. and another in Europe.

Bronze editions of Definitive Study for the Head of Balzac (1897) were initially cast by Georges Rudier nearly fifty years after Rodin’s death, from the plaster studies made in preparation for the monument and left behind in the artist’s studio. The study can be found at the Musée Rodin (Meudon, France) with editions found in the collections of Cleveland Museum of Art (Cleveland, Ohio, U.S.), Baltimore Museum of Art (Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.), Chrysler Museum of Art (Norfolk, Virgina, U.S.), Legion of Honor (San Francisco, California, U.S.), Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, (South Hadley, Massachusetts, U.S.), The Hirschorn, (Washington, D.C., U.S.), The Kreeger Museum (Washington, D.C., U.S., two copies in the National Gallery of Art (Washington, D.C., U.S.), Maryhill Museum of Art (Goldendale, Oregon, U.S.), the Brooklyn Museum (New York City, New York, U.S.), McMullen Museum of Art at Boston College (Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.), The Museum of Modern Art, (New York City, New York, U.S.) as well as a plaster at the Nasher Sculpture Center (Dallas, Texas, U.S.).

[1] An unauthorized cast of an original authorized casting.

[2] Alexis Rudier.

[3] This is to protect Campbell from encroachments of Rodin’s authorship.

Dross

Cooper Campbell

2020

Bronze, unknown heavy metals

9 x 9 x 6 inches

Dross is the term for material impurities of a given alloy or metal that has formed on the surface of liquid metal during the casting process. They are primarily oxides that are produced by the extreme heat necessary for the casting process—as well as tertiary contaminants that may exist in the casting stock.

Dross is absolute waste. Due to its unreliable and unknown make up it is unusable in any continued casting process and unrecyclable as a byproduct.

Dross is a concretion of this cast off and waste materials bound into a consolidated mass by a matrix of bronze.

Consignment, Ormolu and Blue Glass Centerpiece with Floral Arrangement

Louis Constant Sévin for the Barbedienne Foundry,

Cooper Campbell, Consigned by Colin Ross, Flowers from Saffron; Arranged by Grayson Scott

1880, 2021

Cobalt glass, ormolu bronze (gold), flowers

An ormolu bronze vase [1], decorated with medallions of putti and trophies of musical instruments lined with cobalt blue glass, designed by Louis Constant Sévin [2] for the Barbedienne Foundry [3], cast 1880, Paris. Consigned to gallery eyes never sleep, LLC from the New York City antiques dealer M&M Gallery for the exhibition.

The vase features a bouquet of primarily French flora: White Gentian, Chamomile, Heather, Paper Reed and various American Grasses arranged by florist Grayson Scott. The bouquet will remain in the vase for the duration of the consignment.

[1] A type of gilding, hi-karat gold is dissolved in mercury and applied to a bronze substrate, the piece is then fired in a kiln driving off the mercury leaving a gold coating. Ormolu gilders rarely lived past thirty.

[2] Louis-Constant Sévin (1821-1888). A well known french ornamentalist, works can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Carnegie Museum, Musée d’Orsay, amongst others. Officer of the French Legion of Honor.

[3] Ferdinand Barbedienne (1810-1892). A french Founder and industrialist, credited with creating one of the largest industrial art production monopolies in modern history.

Louis Constant Sévin for the Barbedienne Foundry,

Cooper Campbell, Consigned by Colin Ross, Flowers from Saffron; Arranged by Grayson Scott

1880, 2021

Cobalt glass, ormolu bronze (gold), flowers

An ormolu bronze vase [1], decorated with medallions of putti and trophies of musical instruments lined with cobalt blue glass, designed by Louis Constant Sévin [2] for the Barbedienne Foundry [3], cast 1880, Paris. Consigned to gallery eyes never sleep, LLC from the New York City antiques dealer M&M Gallery for the exhibition.

The vase features a bouquet of primarily French flora: White Gentian, Chamomile, Heather, Paper Reed and various American Grasses arranged by florist Grayson Scott. The bouquet will remain in the vase for the duration of the consignment.

[1] A type of gilding, hi-karat gold is dissolved in mercury and applied to a bronze substrate, the piece is then fired in a kiln driving off the mercury leaving a gold coating. Ormolu gilders rarely lived past thirty.

[2] Louis-Constant Sévin (1821-1888). A well known french ornamentalist, works can be found in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Carnegie Museum, Musée d’Orsay, amongst others. Officer of the French Legion of Honor.

[3] Ferdinand Barbedienne (1810-1892). A french Founder and industrialist, credited with creating one of the largest industrial art production monopolies in modern history.

Billet (Copper)

Cooper Campbell with assistance from Michale Carbone and Ha-Lan Van

2020

Copper

3 x 3 x 34 inches

Copper can first observed in the material record of humanity roughly 8,700 BCE the first known example of human manipulation of this metal (or any metal) being a small pendant found in what is now Northern Iraq [1] that appears to be hammered out of “native copper” or naturally occurring deposits of relatively pure copper metal. Additional examples of decorative objects wrought from native copper have been found in Cyprus, Northern Iran [2] and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula [3] both dating back to roughly 7000 BCE.

Over the course of the intervening millenia Copper has been one of the most instrumental materials in human technological advancement; first used as decorative objects (Like the Iraqi pendant) that dually functioned as currency, copper was quickly utilized in tooling before being retasked during the industrial revolution as electrical wiring–its ductility and conductivity allowing for the electrification of modern society.

Cast from both industrial and domestic scrap material (electrical wiring, plumbing line and fittings, electric motor windings, computer parts, decorative figurines, american pennies, etc) purchased from Steve Cook at spot price per pound the material present in Billet (Copper) was cleaned and partially refined before being cast and machined down a billet weighing exactly one-hundred pounds.

[1] Radetzki, Marian. “Seven Thousand Years in the Service of Humanity—the History of Copper, the Red Met- al.” Resources Policy, vol. 34, no. 4, 2009, pp. 176–84. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2009.03.003.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Special thanks to: Tom and Jan Campbell, Rory Campbell, Michael Carbone, Tommy Celt, Jen Conjerti, Seve Cook, Amelia Farley, Magdalena Galen, Joann Lunt, Ivan McClean, Ken Reed, Lucy Raven, Colin Ross, Ha-Lan Van, Margaux Wheelock-Shew, Lucas Zeeburg, and Richard Zeemer.

Cooper Campbell with assistance from Michale Carbone and Ha-Lan Van

2020

Copper

3 x 3 x 34 inches

Copper can first observed in the material record of humanity roughly 8,700 BCE the first known example of human manipulation of this metal (or any metal) being a small pendant found in what is now Northern Iraq [1] that appears to be hammered out of “native copper” or naturally occurring deposits of relatively pure copper metal. Additional examples of decorative objects wrought from native copper have been found in Cyprus, Northern Iran [2] and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula [3] both dating back to roughly 7000 BCE.

Over the course of the intervening millenia Copper has been one of the most instrumental materials in human technological advancement; first used as decorative objects (Like the Iraqi pendant) that dually functioned as currency, copper was quickly utilized in tooling before being retasked during the industrial revolution as electrical wiring–its ductility and conductivity allowing for the electrification of modern society.

Cast from both industrial and domestic scrap material (electrical wiring, plumbing line and fittings, electric motor windings, computer parts, decorative figurines, american pennies, etc) purchased from Steve Cook at spot price per pound the material present in Billet (Copper) was cleaned and partially refined before being cast and machined down a billet weighing exactly one-hundred pounds.

[1] Radetzki, Marian. “Seven Thousand Years in the Service of Humanity—the History of Copper, the Red Met- al.” Resources Policy, vol. 34, no. 4, 2009, pp. 176–84. Crossref, doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2009.03.003.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

Special thanks to: Tom and Jan Campbell, Rory Campbell, Michael Carbone, Tommy Celt, Jen Conjerti, Seve Cook, Amelia Farley, Magdalena Galen, Joann Lunt, Ivan McClean, Ken Reed, Lucy Raven, Colin Ross, Ha-Lan Van, Margaux Wheelock-Shew, Lucas Zeeburg, and Richard Zeemer.

Cooper Campbell (b.1994, Portland, OR) lives and works in Queens, NY. Campbell has exhibited at eyes never sleep, New York, NY, organized by Octagon (2021); The Cooper Union, New York, NY (2017, 2014); and Trust Gallery, Richmond, VA (2014). In 2019, Campbell completed the Interstate Projects Studio Residency, New York, NY. Campbell received his BFA in 2017 from the Cooper Union School of Art, New York, NY. eyes never sleep is a research-based exhibition space centered around curatorial collaboration and editorial initiatives. |